Bruce Caslow says I was “running for pope”, and I really was! There was only one voter, but I was hoping He would work some great miracle and elevate me to that high office. As I was walking back to the Vatican from Roma Termini, I was crying, and crying out to God, saying that even if He did, I would have no idea what to do with it. I soon realized that was not true. I knew I’d need to be guided by prayer every step of the way.

Continue reading “Running for Pope”The Way the World Is

I have often heard the phrase “that’s just the way the world is”.

Here’s the way the world is, as I see it:

- This world is basically unjust. Just because you hand someone a sandwich doesn’t mean you get a reward for your effort. This is just the way the world is.

- To get a reward for their work, most people refuse to provide goods or services unless they get paid.

- Capitalism teaches that behaving in this way benefits society, and that maximizing your profit is what benefits society the most.

- Socialism teaches that the way to overcome these injustices is for the government to run everything.

- Christianity teaches that what God wants is to prioritize selfless love. Forget about what benefits society; prioritize God.

- The “right” preaches a watered down Christianity that teaches we should split our lives into two parts. Some of the time we’re preaching the Gospel and helping the poor; some of the time we’re running a business and taking care of ourselves.

- The “left” preaches that we don’t really need God at all and the government will fix these injustices.

- The Book of Revelation tells us that humanity will never fix these problems, that we’ll never invent a system of government that does, and that left to our own devices, human beings will eventually exterminate ourselves.

- From beginning to end, from the Garden of Eden to the New Jerusalem, the Bible preaches a decidedly anti-populist message. The majority are immoral; only a minority are righteous.

- This society, like almost all human society, is systemically discriminatory, anti-Christian, and oppressive. It is, however, better than many others. At least I can write this on my website without being arrested by the police.

- When Jesus says “…I have chosen you out of the world. That is why the world hates you” (John 15:19), he’s not just talking about the Roman Empire of two thousand years ago. Jesus’s message is timeless and universal.

My Advice to the Church

How would I advise the Roman Catholic Church?

First, end the schism. Admit protestants to full communion, and do so in the following way. Give discretion to local bishops to set their own guidance on who can receive the Eucharist. Many of the bishops already exercise this discretion; they’re just called Methodists or Baptists, etc. Issue guidance from Rome for those bishops who choose to follow it, and that guidance is to administer the Eucharist to all those who accept Jesus Christ as their Lord and Savior. Don’t excommunicate anybody if they won’t do this.

Next, open the religious communities to couples and families. Presumably they were already opened to protestants in the first step. Recognize that the “widows” spoken of in Acts 6:1 were probably admitted to the church in that state – it wasn’t old enough for them to have joined as young women. End the caste division in the church where we have religiosos and laity. Religious community, in some form or another, is the preferred organizational style for the saints.

Communities will probably attract a crowd of homeless followers. They should be accommodated to the greatest extent possible. Provide space for tent cities, and don’t neglect the need for basic hygiene such as toilets and showers. Organize food banks and community feedings.

Preach the authentic Christian gospel. Quit focusing so much on sexuality and teach against the economic immorality of the majority. Our default answer to most requests should be “yes, of course” instead of “here’s how much it will cost”. It’s so hard to believe that God will give us the greatest gift of eternal life for free, when we won’t let people fly on an airplane for free.

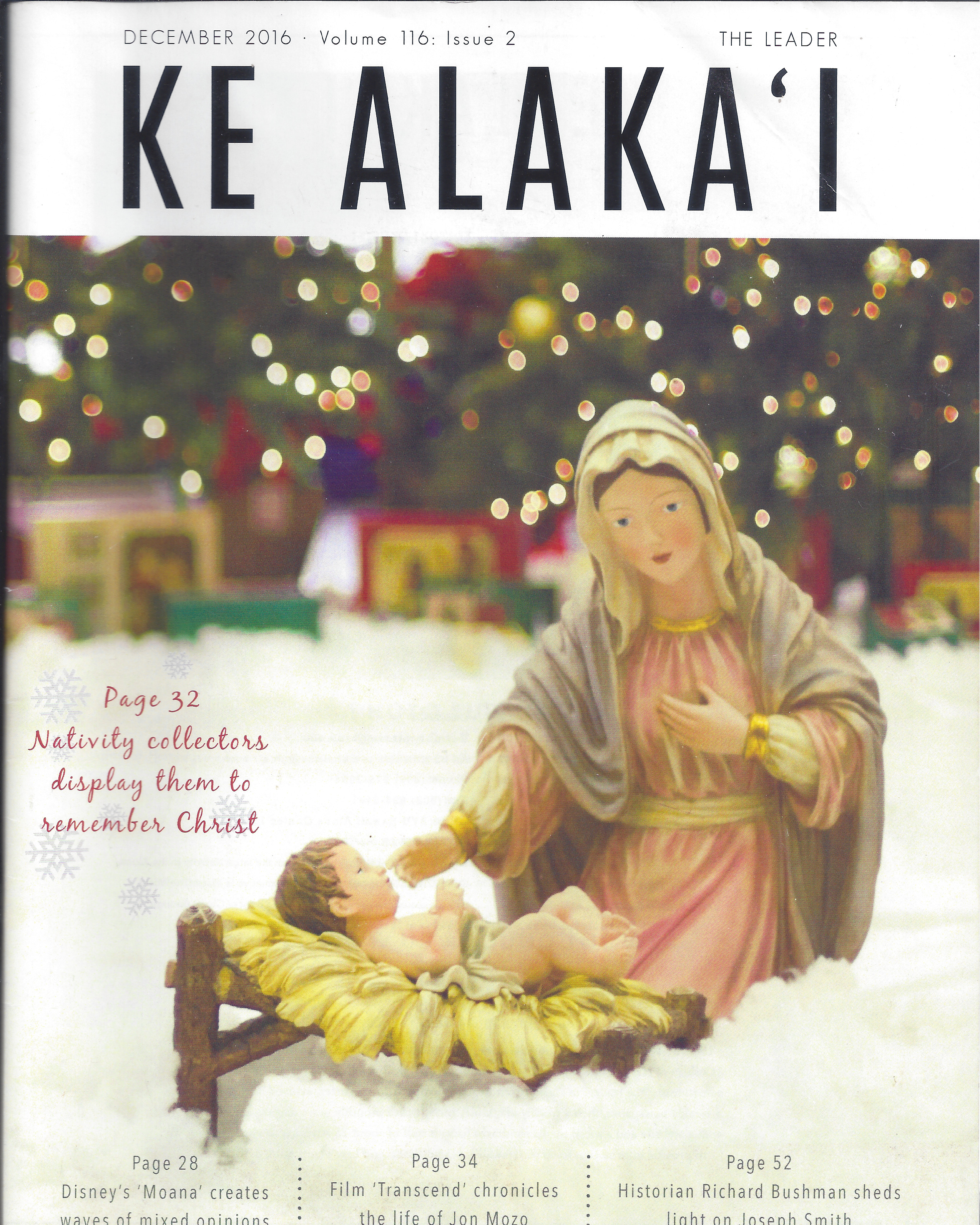

Ke Alaka’i

I spent several months in Laie, Hawaii, where the local college magazine gave me some very good press.

Continue reading “Ke Alaka’i”

An Open Letter to Surfing the Nations

My name is Brent Baccala. Some of you know me only as the man in the white robe holding the sign that reads “Surfing the Nations is a Fraud”. I don’t particularly like the sign, but it’s been given to me by God. I’d rather just stand in front of Surfer’s Church with a microphone and preach, but Tom Bower will not allow that to happen. Let me explain, briefly, my history with STN, tell you what has happened over the last month, and summarize the message that I wish you to hear.

Give up everything you have

Luke 14:33

How are we to understand this passage? First, note that Jesus is talking about discipleship, not salvation. Salvation is being saved from sin and evil, it is deliverance from destruction. A disciple is a convinced adherent of Jesus Christ, who accepts and assists in spreading his doctrines (the definitions are from the Merriam-Webster dictionary). The difference is that you might be able to enter heaven (salvation) without becoming a disciple of Christ. More on that later.

Enter through the narrow gate

“Enter through the narrow gate. For wide is the gate and broad is the road that leads to destruction, and many enter through it. But small is the gate and narrow the road that leads to life, and only a few find it.

Matthew 7:13-14

How are we to understand this passage? It certainly doesn’t read as a ringing endorsement of democracy! Indeed, the Bible warns us to be wary of populist thinking, and indicates that most people in this world are headed for destruction.

Philosophy of Christian Education

I write from the perspective of a teacher, one who has taught principally adults, sometimes adolescents, and never children. I write from this perspective while remaining aware that the ultimate responsibility for the education of children lies with their parents, aware also of the passions aroused in parents whenever issues of child rearing are discussed.

I will note only in passing those unfortunate and, unfortunately, too common, occurrences when parents dispute and disagree, perhaps even to the point of divorce. Family, teachers, schools and courts are then placed into the unwanted but unavoidable position of arbitrating between father and mother to determine what is best for their children. Instead, for this essay, I will limit myself to those happy cases where the parents agree on the educational course of their children, and further agree that a Christian education is desired.

It does not follow that the students must be Christians.

Especially in primary and secondary school, the parent, not the student, is likely the driving force behind the enrollment. Furthermore, adolescents are transitioning to adulthood, and not only may be asking philosophical questions about the existence and nature of God, but are also making more assertive and independent behavioral choices.

…Always be prepared to give an answer to everyone who asks you to give the reason for the hope that you have…

1 Peter 3:15

So the Christian teacher, as St. Peter advises disciples in general, should be prepared to give answers to questions of faith, in addition to whatever the lesson plan happens to be for the day.

Granted, then, that the teacher is a Christian with a personal relationship with God and a personal testimony that is compatible with the parent’s expectations, how then, to prepare students in a Christian school? What, first and foremost, is the goal?

Jesus came to them and spoke to them, saying, “All authority has been given to me in heaven and on earth. Go, and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all things that I commanded you. Behold, I am with you always, even to the end of the age.”

Matthew 28:18-20

Thus, the ideal teacher is not only a Christian, but a disciple, because it is for discipleship that we seek to prepare our youth.

A disciple may not be a professional teacher. A disciple could only be a professional teacher if called predominately to that vocation by God, and none of the great historical disciples were. Neither Moses, nor David, neither Peter nor Paul, not Benedict, not Francis… none of them were professional teachers. Perhaps Martin Luther came as close to a teaching vocation as any great Christian disciple, but I still argue that Luther’s role as a theology professor at Wittenberg was secondary to his greater calling in life.

So, the ideal Christian teacher is a disciple first, and a teacher second. One could argue that the ideal Christian teacher would be both, but that would relegate everyone on the previous paragraph’s list, from Moses to Francis, to secondary status. Perhaps we could use them as subs.

I do not claim that there are no disciples called to serve as professional teachers. I merely point out that many are not, and because our primary goal is to train the youth as disciples, a disciple, even if not a professional teacher, is preferable to someone who has been teaching calculus for twenty years but has no real sense of being guided by the Holy Spirit. I further contend that your “average” Christian disciple (whatever that may be) will have a greater calling in life than simply teaching mathematics.

So, the ideal Christian teacher is a disciple in the strongest possible sense, possesses a mastery of the subject material being taught, is capable of teaching both discipleship and the subject at hand, and whose views on questions of morals and dogma are compatible with those of the parents, who bear the ultimate responsibility for the upbringing of their children.

Adolescents, “vacillating between infancy and youth” (Octavio Paz), are fully capable of leaving home, getting a job, or just living homeless on the streets. Yet their parents continue to support them, provide them with shelter and nourishment, arrange for their continuing education, and the adolescents generally accept this arrangement. Why? Life, in its brutality and its beauty, in its love and its violence, in its glorious success and its crushing failure, is, for them, yet something that mostly passes by on the television screen.

“I’m dropping you off in downtown L.A. with no money and just the clothes you’re wearing, son. If you need food or shelter, pray to God. He provided for Haggar in the desert.” (Genesis 21)

For better or for worse, few parents are prepared to make this offer and few adolescents are prepared to accept it. Perhaps it’s better, after all, for the adolescent to wait a few more years, perhaps until their early twenties, before deciding whether to take Jesus up on his offer to sell all of your worldly possessions, give your money to the poor, and become a disciple of Christ (Luke 12).

In the mean time, those of us who have made that choice wish to present it as what it is: the most important decision of any human being’s life. We do not wish to neglect discussing it, nor do we wish to sugar coat its consequences. Neither silence nor spin is acceptable. Of what do we wish to inform adolescents?

A ground study of the Bible is essential. Those of us raised on the stories of Abraham and Moses, of Ezekiel and Elijah, of Jesus and Peter might tend to take this for granted. Everyone knows the Bible stories, right? Well, not everyone, at least not until the stories are told, and without a sense of where you’ve come from, how can you develop a sense of where you are?

Some knowledge of post-Biblical Christian history is important, too. It’s been two thousand years since the last of the scriptural texts were written, and a lot has transpired here on planet Earth. While nothing should supplant the teachings of the Messiah as authoritative truth, young Christians should know something of how the church has evolved over the centuries, of Benedict and Francis, of Martin Luther and of Mother Teresa. The schisms of those years must be mentioned too, at least so as to understand the Aryan controversy or the Church of Later Day Saints.

These topics can be handled, perhaps are best handled, in the context of Sunday School or religion classes. Yet it seems counter productive to present spirituality as a specialized discipline, something as unexpected from the history teacher as a lecture on photosynthesis. That would present Christianity as a career choice, rather than as a life choice. So for practical guidance on how to live a Christian life, as well as creating a school environment where Christian virtue is displayed, the entire faculty should be Christians, and Holy Spirit should move in their lives.

To achieve this, perhaps it’s best to regard Christian education as a ministry, and the Christian school as a mission. From this perspective, the students are junior disciples in a Christian community, a community that should take time to pray and worship together, to seek God’s will, both individually and collectively, as well as developing private prayer, personal discernment, and spiritual guidance. Worship services, fellowship, prayer retreats, mission trips and evangelism seem not only to be good ideas, but essential components. Ideally, a Christian school should be but one ministry within a fully developed Christian community, so that the students may witness and learn from fully developed and functional discipleship.

Discipleship. Mission. Community. An overriding sense that God must be in charge. These are the guiding concepts of Christian education, just as they guide Christian life.

My Confession

My Response to Thomas Friedman

In his best seller “The World is Flat”, Thomas Friedman identifies ten “flatteners” that are leveling the global economy; forces such as outsourcing, offshoring, supply chaining, and the collapse of the Soviet empire. His fourth flattener is open source software. None of his issues are particularly new, but it is Friedman’s treatment of them, notably both his and Bill Gates’s shocking misunderstanding of free software, that raises some of the most provocative questions of a provocative book.